What consumer goods can teach us about buying boring businesses and building empires

Walk down any household aisle and you’ll see brands like Arm & Hammer, OxiClean, Orajel, Trojan, First Response, and Nair. These products are everywhere — in your home, your parents’ home, and probably even in your grandma’s medicine cabinet.

What you might not know is that all of those brands — and dozens more — are owned by a single company: Church & Dwight, a $25 billion public company hiding in plain sight.

They didn’t build these brands.

They bought them.

And in doing so, they wrote one of the most underrated acquisition stories in American business.

Act 1: The Origin Story — From Baking Soda to Buyouts

Church & Dwight was founded in 1846 — nearly two centuries ago — with a single product: baking soda. Back then, it was a commodity, used for cleaning, cooking, and deodorizing. The product hasn’t changed much, but the company sure has.

For much of its early life, Church & Dwight was a slow-moving, regional manufacturer. They made one product and made it well. But like any good long-term operator, they realized that growth wouldn’t come from squeezing pennies out of a commodity. It would come from owning more shelves — not just with their own brand, but with other trusted brands, acquired and scaled under a unified operation.

Their real transformation began in the late 1990s and early 2000s. That’s when Church & Dwight turned on its acquisition engine.

Their thesis?

There are great brands languishing inside mismanaged companies.

Buy the brands.

Cut the waste.

Modernize operations.

Optimize distribution.

And print cash.

In short: they didn’t buy to disrupt — they bought to steward.

Act 2: The Playbook — Buy Boring, Operate Brilliantly

Church & Dwight didn’t chase trends. They didn’t care about cool. They weren’t trying to invent the next big thing.

Instead, they quietly bought up brands that:

- Had been around for decades

- Had strong brand awareness

- Served essential, recurring needs

- Were under-marketed or poorly managed

- Could benefit from better supply chains, marketing, and pricing discipline

Some of their biggest wins include:

- Trojan Condoms (2001): Acquired through the Carter-Wallace deal. Trojan had nearly 70% market share in condoms but was under-leveraged in adjacent categories. Church & Dwight expanded the product line, improved packaging, and modernized advertising.

- OxiClean (2006): Bought from Orange Glo International after founder Billy Mays made it a household name on infomercials. Under Church & Dwight, it went from cult favorite to category leader in stain removers.

- Orajel (2008): Bought from Del Labs. Already a trusted brand for oral pain relief, Church & Dwight revamped packaging, cross-promoted it with other hygiene brands, and streamlined distribution.

- Nair, First Response, Spinbrush, Waterpik, and several others followed.

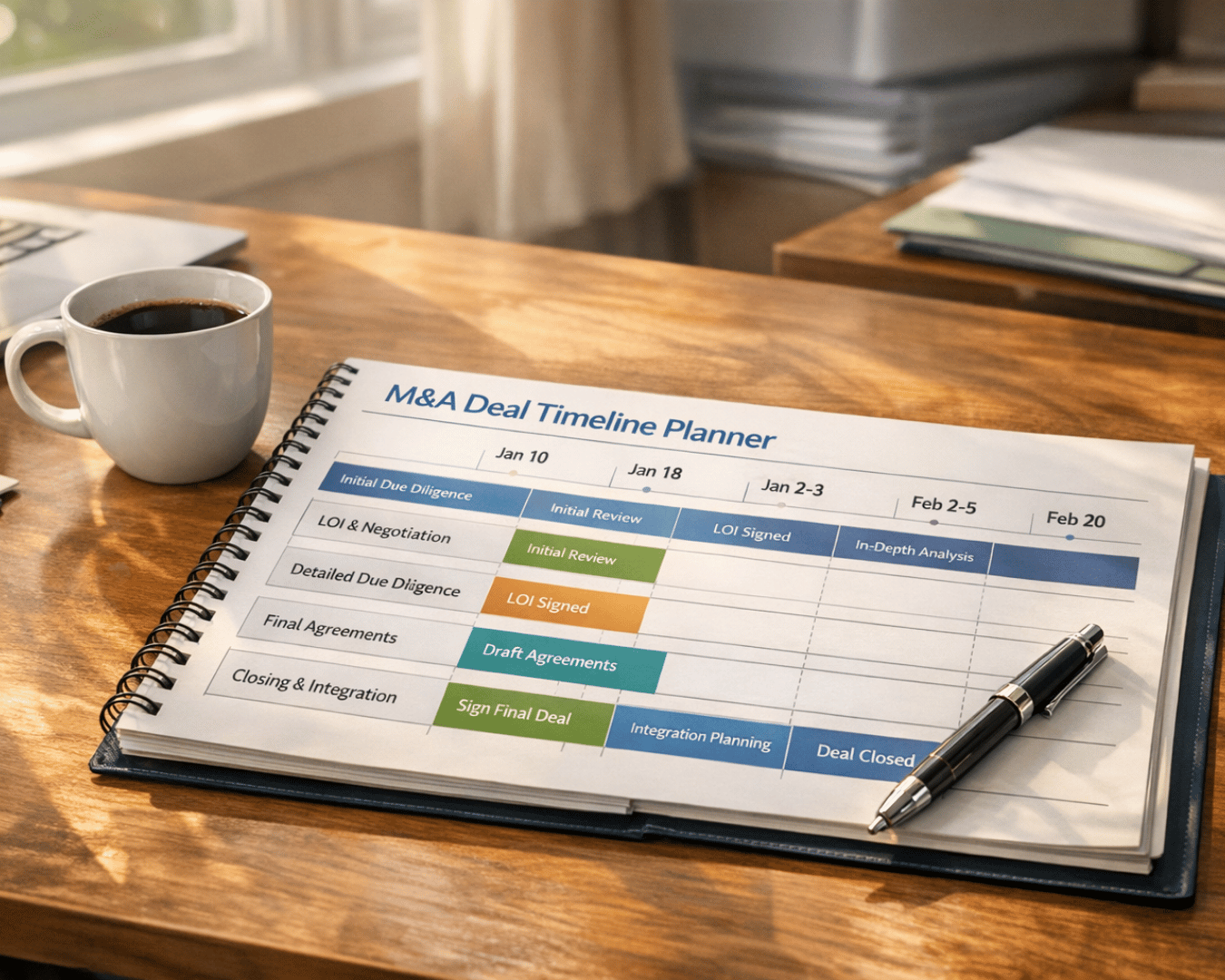

Each acquisition followed a clear process:

- Acquire a trusted but neglected brand

- Cut unnecessary costs (corporate overhead, bloated ad budgets)

- Apply their operational playbook (retail distribution, supply chain, CPG pricing strategy)

- Cross-promote with other owned brands

- Use existing retail relationships to win shelf space

- Reinvest profits into repeatable growth

Instead of running each brand like a separate business, they plugged every acquisition into a centralized infrastructure. This created massive operational leverage.

Act 3: The Power of Compounding and Operational Leverage

By the 2010s, Church & Dwight had hit its stride.

Unlike Procter & Gamble or Unilever, who built brands in-house and relied on mega-scale marketing, Church & Dwight built its empire on niche domination. They didn’t want to own everything. They just wanted to own repeat-purchase, non-cyclical, high-margin brands in very specific verticals.

And they succeeded — spectacularly.

From 2000 to 2023, Church & Dwight grew its market cap from under $1 billion to over $25 billion.

They became a case study in:

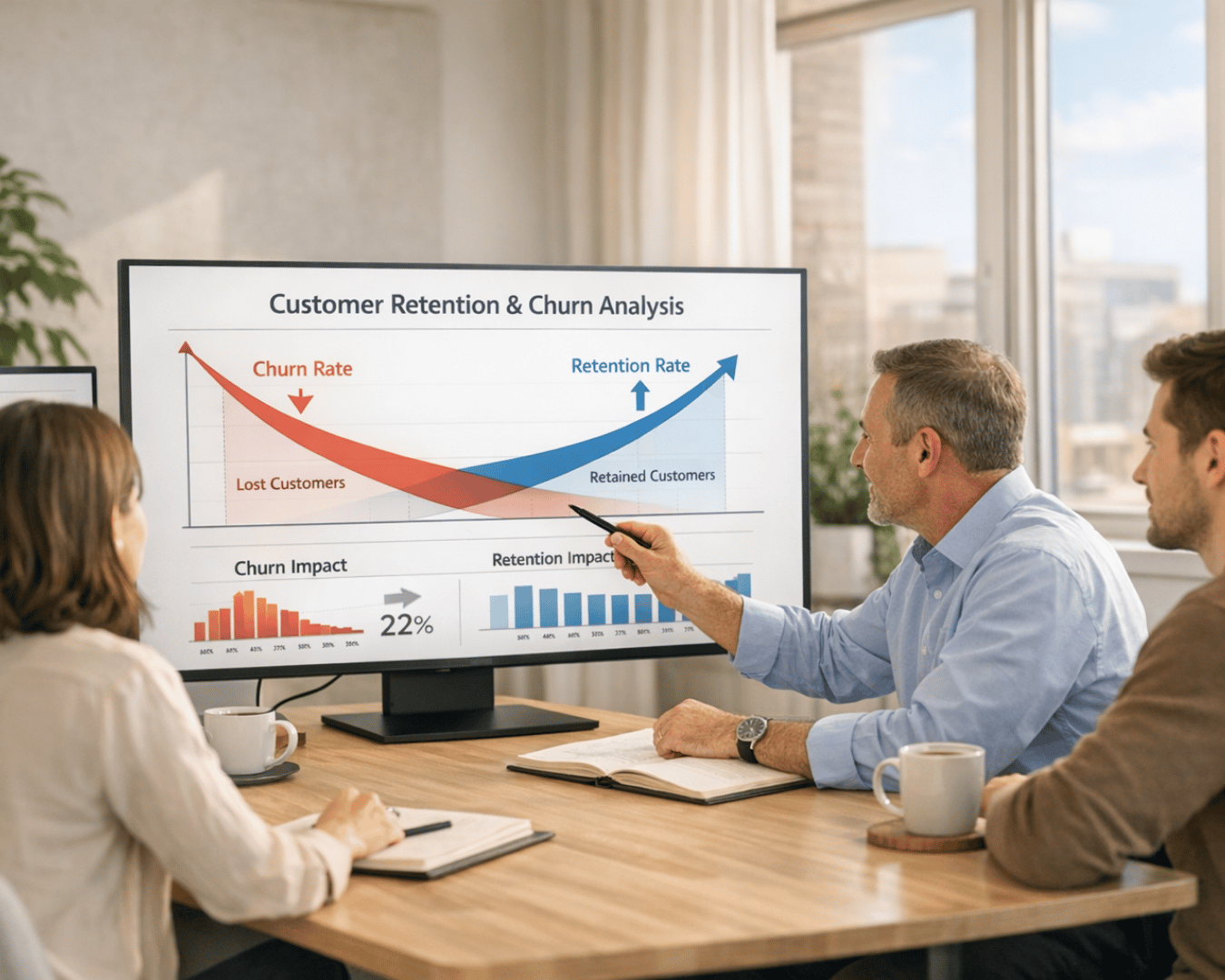

- Capital efficiency: ROI on acquired brands was consistently high

- Margin expansion: through centralized ops, pricing power, and COGS control

- Sustainable growth: fueled by recession-proof, necessity-driven products

- Brand flywheels: using one brand’s shelf presence to boost another’s

The best part?

Very few people outside of Wall Street noticed.

While the world focused on unicorns, IPOs, and tech startups, Church & Dwight quietly compounded shareholder value — quarter after quarter, decade after decade — through Main Street-style acquisitions at Fortune 500 scale.

Act 4: The Lessons for Acquisition Entrepreneurs

You don’t need to be a Fortune 500 company to apply this playbook.

In fact, this strategy works better at the lower middle market level — where inefficiencies are higher, prices are lower, and private owners are more likely to sell.

Here are five key lessons Church & Dwight offers every searcher, operator, or fund manager:

1. Brand Equity is Undervalued

Most people don’t know how valuable a legacy brand can be. But if customers already trust a product — and you can improve how it’s sold, marketed, or delivered — you have a huge head start. Buying brand equity is often faster (and cheaper) than building it.

2. Operations Are the Real Moat

Church & Dwight didn’t invent new products — they out-executed the competition. If you have strong systems, people, and processes, you can buy mediocre businesses and turn them into great ones.

3. You Can Be a Steward, Not a Founder

You don’t need to start from scratch to build something valuable. Most businesses already have product-market fit — they’re just mismanaged, under-capitalized, or out of touch with modern growth practices.

4. Non-Cyclical, Repeatable Products Win

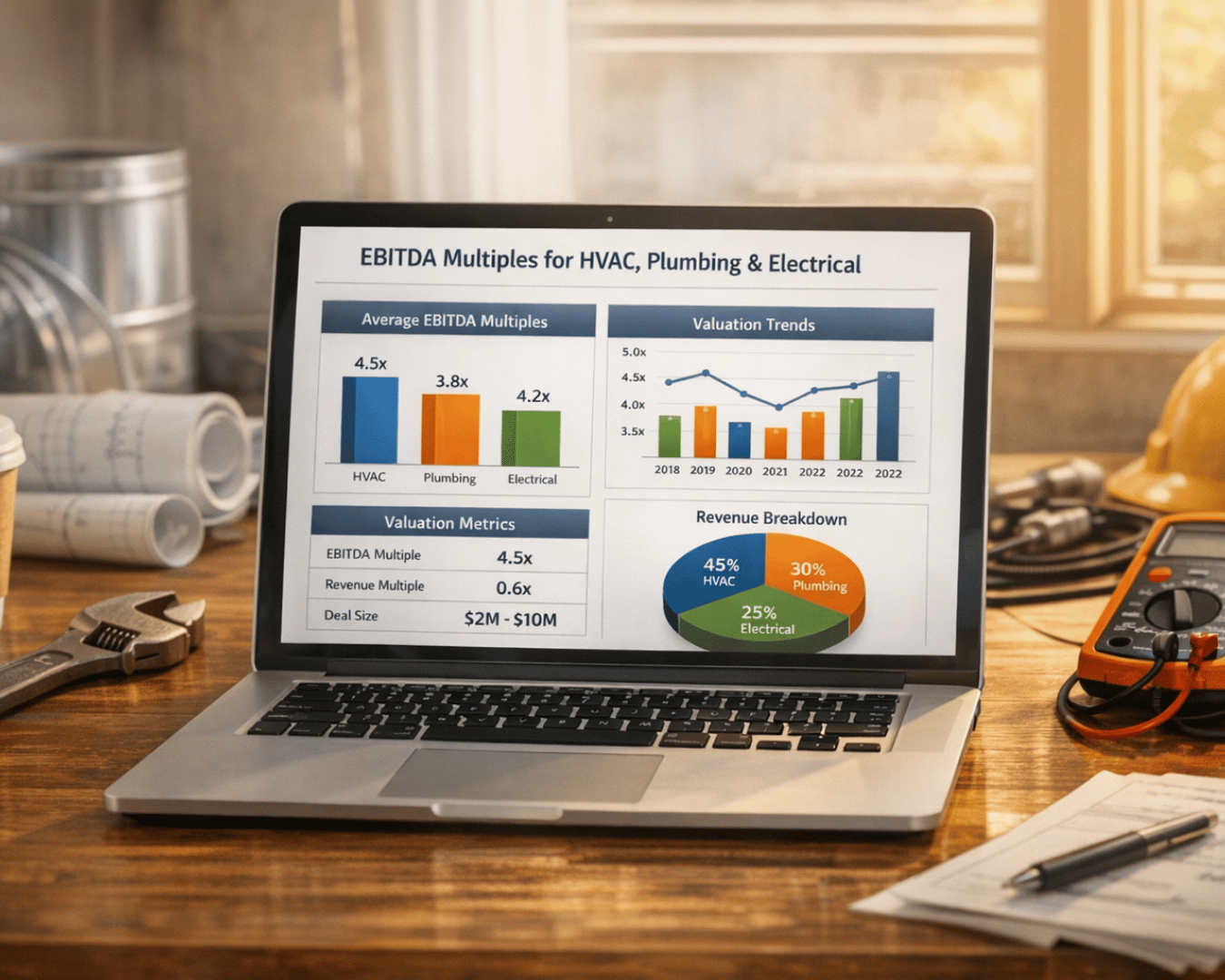

They focused on essential products — oral care, cleaning, hygiene, family planning — not fads. That’s the same principle guiding the best acquisition entrepreneurs today: HVAC, plumbing, accounting, pest control, landscaping, and other boring-but-essential services.

5. Great Acquirers Think in Decades

Church & Dwight didn’t flip businesses. They integrated, scaled, and held for the long haul. Their return wasn’t just financial — it was durable. True wealth comes from patient capital and compounding, not flashy exits.

Act 5: Applying the Playbook on Main Street

What does this mean for the average search funder or acquisition entrepreneur?

It means the next $25 million, $250 million — or even $2.5 billion — opportunity isn’t in Silicon Valley or crypto.

It might be in Omaha.

Or Tulsa.

Or wherever there’s a legacy business with great bones and bad systems.

It’s the landscaping company with loyal customers and zero CRM.

The HVAC company doing $5M in revenue but no inbound marketing.

The industrial distributor that’s never optimized pricing.

The 50-year-old janitorial brand with a retiring owner and no digital presence.

Just like Church & Dwight, you don’t need to invent a category.

You just need to find overlooked brands or businesses, fix what’s broken, and hold.

Whether you’re a solo searcher, a self-funded operator, or running an investment fund, the strategy is timeless:

- Acquire quality cash flow.

- Improve margins, process, and growth.

- Stack acquisitions to build scale.

- Use cash to reinvest, repay, or re-acquire.

- Hold, compound, and grow quietly.

Final Thought: There’s Power in Obscurity

Most people don’t know the name Church & Dwight.

But they know the products.

They’ve trusted them for decades.

And that trust — built slowly, consistently, and quietly — has created one of the most enduring, profitable business empires in America.

There’s a lesson there.

You don’t need to be famous.

You just need to operate with focus, discipline, and patience.

Buy boring.

Operate brilliantly.

And watch what happens.

Want to build your own portfolio of cash-flowing acquisitions?

Clearly Acquired helps buyers find deals, get financing, and grow with confidence.

Start your acquisition journey →

%20%20Process%2C%20Valuation%20%26%20Legal%20Checklist.png)

%20in%20a%20%2420M%20Sale..png)

%20vs.%20Conventional%20Loans%20for%20business%20acquisition.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)